1909 – 1942

On Badwell Ash WWII War Memorial

Leslie was born in Semer, near Hadleigh, Suffolk on 3rd February 1909, the son of Herbert and Marie Holder.

He is shown as living at Manor Farm, Kersey Tye, Suffolk on the 1911 census with his father, Herbert aged 36, a Horseman on Farm, his mother, Moire, aged 37 and six brothers and sisters. Stanley aged 14, Caleb aged 12, Wilfred aged 10, Eric aged 8, Winfred aged 6 and Bertram aged 4.

Leslie (known to his family as Les) and his family moved to Langham (the next village to Badwell Ash).

Les married Elsie Sarah Morley on 3rd July 1935. They had two children, the first of whom died at birth in 1939 and John Herbert Holder who was born in 1941. Les had joined the Navy in February 1927 at HMS Pembroke II (Chatham Barracks) as a Stoker Second Class. During the war as Les was away a lot, rather than live alone Elsie moved in with her parents in 1940 at number 9 The Council Houses on Hunston Road, just after they were built,

Military

His Naval career started on 28 February 1927 in Chatham, Kent.

When home on leave he spotted his future wife Elsie Morley who lived in Badwell Ash, and worked for the Martineau Family in Walsham Le Willows. They married on 3rd August 1935 at St Mary’s Church Badwell Ash.

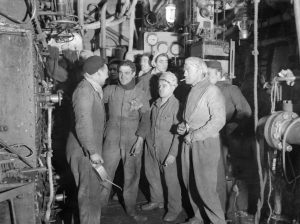

At the time of the wedding Les had been promoted to the rank of Petty Officer and Stoker, which meant spending most of his time on ships was below decks in their boiler rooms.

His last vessel HMS Curacoa (named after the Caribbean Island of Curaçoa) was a light cruiser built in 1917 which was on escort duty to the convoys. Les was still a Petty Officer and Stoker and being an old ship, built during WWI, she was coal fired.

Curacoa was escorting the Luxury Ocean Liner R.M.S. Queen Mary which was 1019 feet long, had a beam of 118 feet, weighed 81,000 tonnes, and had been converted to a troop ship for the duration of the war. She had been painted a pale shade of grey (and was known as “The Grey Ghost”) and could travel at a maximum of 30 knots which meant she could easily outrun any U-Boat.

Adolf Hitler had offered any U-Boat Captain a bounty of $250,000 and the German Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, for sinking either the Queen Mary or Queen Elizabeth.

During October 1942 the Queen Mary was sailing from New York to Greenock in Scotland loaded with 10,000 American troops of the 29th Infantry Division. She would follow a zig-zag course to reduce the U-Boat threat and the escorts would sail with her for the last few miles to the U.K. On this occasion, she was joined by H.M.S. Curacoa and the destroyers H.M.S. Bramham and H.M.S. Cowdray to provide anti-aircraft cover north of Ireland for the last leg into Scotland.

On 2nd October it was to be zig-zag course number 8. The course was changed frequently to confuse the enemy. Curacoa was an old vessel (built in 1917) and could take some time to get up to her maximum speed of 25 knots, Les’s job as a stoker was to keep her steam pressure high to ensure she was steaming as fast as possible.

Queen Mary usually sailed at a minimum of 28 knots and was on strict orders not to stop under any circumstances. Whilst she would change course every 4 to 8 minutes following a zig-zag pattern she would always make sure to maintain her mean course towards Greenock. In the meantime, the escorts would sail in formation with the Queen Mary crossing and re-crossing their course, always ensuring that their main objective of protecting the Queen Mary was maintained. On this occasion there was also air cover for this convoy from a Flying Fortress B17 heavy bomber.

In the afternoon of the 2nd October, various changes of officers on the bridge of Queen Mary were taking place. Captain Illingworth, the Captain of the Queen Mary was in his chart room plotting what time he would arrive in Scotland. Those on the Queen Mary’s bridge had already remarked that Curacoa was rather close to Queen Mary but they tended not to change course as the escorts always made sure they kept out of the way. However, on this occasion the Queen Mary’s Officer in charge did alter the course slightly but, with the Queen Mary travelling at 28 knots and moving at 50 feet per second, to try to turn her away from something in her path would inevitably take several minutes before any course change would take effect. What happened thereafter has long been a matter of debate.

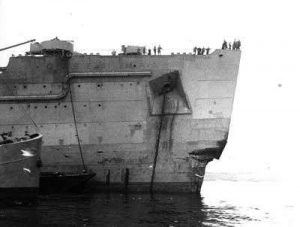

Then disaster struck! The Curacoa turned across the Queen Mary’s bow and, with no chance of her being able to alter course or slow down, the Curacoa was rammed amidships and sliced in two. (Photo Les7)All that was felt on board the Queen Mary was a jolt and not much else. The American soldiers on board Queen Mary could immediately see what had happened. The Curacoa had been cut into two. The stern section, about one third, stayed afloat for 2 minutes with steam and black smoke pouring from the severed pipes. Poor Les was below decks in this section and did not have any hope of escape. The bow section, about two thirds stayed afloat for about another 4 minutes with those on this section only then noticing that the rear end was completely missing! The location of the accident is shown on the map.

Queen Mary was unable stop to pick up survivors due to her orders and had to keep heading towards Scotland. Captain John Boutwood of the Curacoa was able to get out alive but 338 men perished. When the rescue ships arrived, The Bramham and another escort, some of the rescued crew said they should “chuck the Bastard back in! ” as captain’s were supposed to be the last to leave a sinking ship!

There were only 101 survivors due in part to life jackets being thrown overboard by the American troops on board the Queen Mary whose speed was reduced to 14 knots due to the damage to her bows. The Queen Mary signalled S.O.S. to give the position of the tragedy. Two escorts then turned back to pick up the cruiser’s survivors. Of the 338 men who lost their lives some of the bodies were washed up on the coast of Scotland.

Queen Mary finally arrived at the nearest port, Gourock, Scotland where emergency repairs were made patching the bow with 7 tonnes of concrete. Many people wondered what had happened but they had to wonder for a long time, as it was “hushed up” by the Government until after the War. In addition, those who witnessed the collision were sworn to secrecy due to national security concerns.

The Queen Mary limped to Boston, U.S.A. after the temporary repairs were carried out at Gourock where a more permanent repair was undertaken.

The wreck of H.M.S. Curacoa lies in 125 metres of water, and was dived in 2017. However, Under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986, Curacoa’s wreck site is designated a “protected place” and war grave.

Most of the men who perished, including Leslie are remembered on the Chatham Navel memorial in Kent (see picture) and the rest on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial. Those who died after rescue, or whose bodies were recovered, were buried in Chatham or in Arisaig Cemetery in Inverness-shire.

The loss was not publicly reported until after the war ended, although the Admiralty filed a writ against Queen Mary’s owners, Cunard White Star Line in 1943. In 1946 the case was finally heard and January 1947 the Judge in the High Court exonerated the Queen Mary’s crew and her owners from all blame and laid all fault on Curacoa’s officers. The Admiralty appealed this ruling and the Court of Appeal modified it, assigning two-thirds of the blame to the Admiralty and one third to Cunard White Star. The latter appealed to the House of Lords, but the decision was upheld.

Leslie Holder in remembered in Badwell Ash Church on the War memorial in the South Aisle.

His Commonwealth War Graves Certificate can be seen here.

(PDF Les 13)

Leslies’ Naval Record Card can be seen here

Leslie Holder’s great nephew, Dave Steward, who is a member of The Badwell Ash History Society and a Local Historian, Professional Family Researcher and Public Speaker has researched Leslie’s life and wrote this article for the Badwell Ash Heritage website.